|

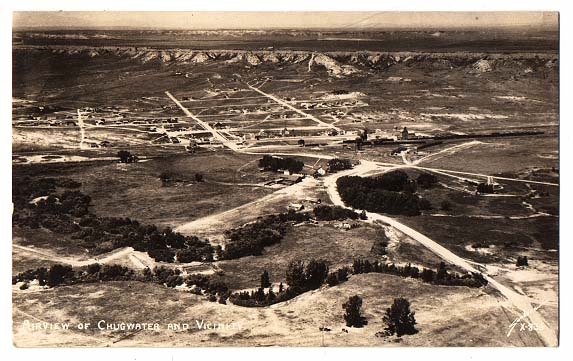

Chugwater, Wyo., 1930's

South of

Chugwater on Iron Mountain Road is the ghost town of Diamond,

and further south in Iron Mountain was the Frontier

Land & Cattle Company, owned by John Coble

and which served as a "home away from home"

of Tom Horn when he was working as a "cattle detective." To the west lies

Bosler, a town which today barely survives.

Horn's cabin is still on the Iron Mountain Ranch near Bosler.

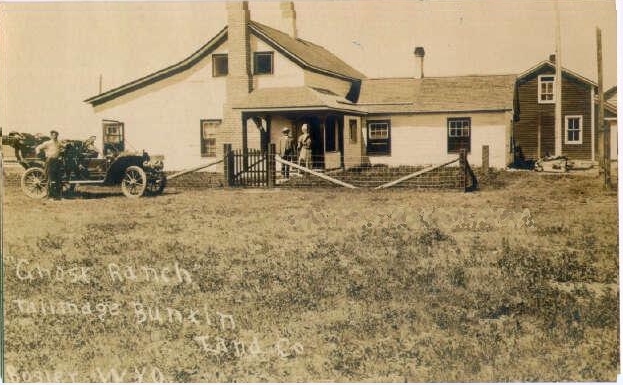

Tallmadge-Buntin Land Co., Bosler, approx. 1910

In August and September 1895, the area was shaken by the unsolved shooting of

two local ranchers, William Lewis and Fred U. Powell. A manuscript fragment by an

unknown author, sympathetic to Tom Horn, describes the killings and their impact [Webmaster's note: If

anyone knows the name of the unknown author, I will be most grateful if you will

E-Mail me.]:

Anonymous Manuscript Fragment

For men who had left cattle alone after getting their first notices had

received no second.

But the day of the deadline came and passed, and the men who had scoffed

at the warnings laughed with satisfaction.

For , with a single exception, nothing had happened to them.

The exception was an Iron Mountain settler named William Lewis

After walking out to his corral that morning, he'd been amazed to

see the dust puff up in front of his feet.

A split second later, the distant crack of a rifle had sounded.

He 'd mounted up immediately and raced with a revolver ready

toward the spot from which he'd estimated the shot had come.

But he had found all of the thickets and points of cover deserted.

There had been no sign of a rifleman and no track or trace to show that

anyone had been near.

Bosler Depot, 1916

Lewis was a man who had made a full - time job of cow stealing

He hadn't even pretended to be farming his spread.

His land had never been plowed.

He had done his rustling openly and boasted about it.

He had received both first and second anonymous notices , and

each time he had accused his neighbors of writing them.

He had cursed at them and threatened them.

He found nothing, but he still refused to give up and move out.

This time Lewis had his own rifle in his hands, and he threw some

answering fire back at the mysterious far - off shot, then spent

most of the day searching out the area.

"I'll be shootin' right back.

I'll be ready next time!" he raged.

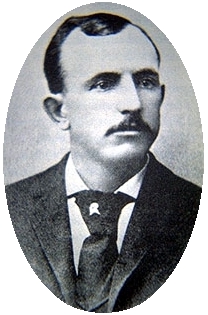

Tom Horn

William Lewis made the rounds of all who lived near

him again, that August morning after a bullet landed at his feet, and once more he accused and threatened everyone.

He was a man , those neighbors testified later, who didn't have a friend

in the world.

He had his chance the very next morning, for exactly the same thing happened again.

"Just let me meet up with that damned bushwhackin' coward face - to - face!"

he exploded.

"That's all I ask."

He never got that chance.

For the unseen, ghostlike rifleman aimed a little higher the third time.

A .30-30 bullet smashed directly into the center of William Lewis' chest.

He slumped against a log fence rail, then tried to lift himself.

Two more shots followed in quick succession, dropping him limp and huddled on the ground.

An inquest was held, and after a good deal of testimony about the anonymous notes,

the county coroner estimated that the shooting had been done from a distance of 300 yards.

Rumors of the offer Tom Horn had made at the Stockgrowers' Association meeting had leaked out by then,

and as a grand jury investigation of the murder got underway, the prosecuting attorney,

a Colonel Baird, ordered that the tall stock detective be summoned for questioning.

It took some time to locate Horn.

He was finally found in the Bates Hole region of Natrona County, two counties away.

Prosecutor Baird immediately assumed he was hiding out there after the shooting and

began preparing an indictment.

But that indictment was never made.

For Tom Horn, it turned out, had a number of rancher and cowboy

witnesses ready and willing to swear with straight faces that

he had been in Bates Hole the day of the killing.

The former scout's alibi couldn't be shaken.

The authorities had to release him.

He immediately rode on to Cheyenne, threw a ten - day drinking spree

and dropped some very strong hints among friends.

"Dead center at three hundred yards, that coroner said!" He'd grin.

"Three shots in that fella 'fore he hit the ground.

You reckon there 's two men in this state can shoot like that."

Publicly, he denied everything.

Privately, he created and magnified an image of himself as a hired assassin.

For a blood - chilling ring of terror to the very sound of

his name was the tool he needed for the job he'd promised to do.

The unknown author continues in the description of the killing of Powell:

Tom Horn was soon back at work, giving his secret employers their money's

worth.

A good many beef - hungry settlers were accepting the death of William Lewis

as proof that the warning notes were not idle threats.

The company herds were being raided less often, and cabins and soddies

all over the range were standing deserted.

But there were other homesteaders who passed the Lewis murder off

as a personal grudge killing, the work of one of his neighbors.

Horn weaving rope

The rustling problem was by no means solved.

Even in the very area where the shooting had been done, cattle were

still disappearing. For less than a dozen miles from the unplowed land

of the dead man lived another settler who had ignored the warnings

that his existence might be foreclosed on; a blatant and defiant rustler

named Fred Powell. "Fred was mighty crude about the way he took in cattle,"

his own hired man, Andy Ross, mentioned later.

"Everyone knew it, but he sort of acted like he didn't care who knew it -- even

after them notes came, even after he'd heard about Lewis, even after he'd been

shot at a couple o' times hisself."

On the morning of September 10, 1895, Powell and Ross rose at dawn and began their day's work.

Haying time was close at hand, and they needed some strong branches to repair a hay rack.

Harnessing a team to a buckboard, they drove out to a willow-lined creek about a half-mile off,

then climbed down and began chopping.

Andy Ross had just started swinging an ax at his second willow when the distant blast of a rifle sounded.

He looked around in surprise, then noticed that Fred Powell was clutching his chest.

The hired man ran over to help his boss.

"My God , I 'm shot!" Powell gasped.

And he collapsed and died instantly.

Ross had no intention of searching for the assassin.

He heaved the dead man onto the buckboard, yelled and lashed at the

team and got out of there fast.

But he brought back the sheriff and several deputies, and to the lawmen the

entire affair seemed a repetition of the Lewis killing. A detailed scouring

of the entire area revealed nothing beyond a ledge of rocks that might

have been the rifleman's hiding place.

There were no tracks of either hoofs or boots.

Not even an empty cartridge case could be found.

Once again, Tom Horn was the first and most likely suspect, and he was brought

in for questioning immediately.

Once again , he shook his head, kept his face expressionless and his voice very calm,

and had a strongly supported alibi ready.

Later, riding in for some lusty enjoyment of the liquor and professional

ladies of Cheyenne, he laid claim to the killing with the vague insinuations he made.

"Exterminatin' cow thieves is just a business proposition with me",

he'd blandly announce.

"And I sort o' got a corner on the market."

"Tom," a friend asked him once,

"how come you bushwhacked them rustlers.

They wouldn't o' stood no chance with you in a plain, straight - out shoot - down."

He had lots of friends, then as always.

Even as he became widely known as a professional killer, nearly every cowboy

and rancher in Wyoming seemed proud to call him a friend.

No man 's name brought more cheers when it was announced in a rodeo.

He explained, "s'posin' you was a nester swingin' the long rope?

Which would you be most scairt of, a dry-gulchin' or a shoot - down.

Yeah, I can see that", the friend was forced to agree.

"But ... well, it just don't seem sportin' somehow."

The tall sunburnt rustler - hunter stared in amazement.

"I seen a lot o' things in my time.

I found a trooper once the Apache had spread-eagled on an ant hill,

and another time we ran across some teamsters they'd caught, tied

upside down on their own wagon wheels over little fires until

their brains was exploded right out o' their skulls.

I heard o' Texas cattlemen wrappin' a cow thief up in green hides

and lettin' the sun shrink 'em and squeeze him to death.

But there 's one thing I never seen or heard of, one thing I just don't

think there is, and that's a sportin' way o' killin' a man."

The unknown writer continues with a description of the impact of the killings on

rustling in Albany and Laramie Counties:

After the first two murders, the warning notes were rarely ignored

The lesson had been learned. The examples were plain.

When Fred Powell's brother-in-law, Charlie Keane, moved into the dead man's home,

the anonymous letter writer took no chances on Charlie taking up

where Fred had left off and wasted no time on a first notice:

"I IF YOU DON'T LEAVE THIS COUNTRY WITHIN 3 DAYS, YOUR LIFE WILL BE

TAKEN THE SAME AS POWELL'S WAS."

This was the message found tacked to the cabin door.

Keane left, within three days.

All through Albany and Laramie counties, other men were doing the same.

Houses of settlers who'd treated the company herds as a natural resource,

free for the taking, were sitting empty, with weeds growing high in their yards.

The small half - heartedly tended fields of men who'd spent more

time rustling cattle than farming were lying fallow.

No cow thief could count on a jury of his sympathetic peers to free

him any longer.

Jury, judge and executioner were riding the range in the form

of a single unknown figure that could materialize anywhere, at any time,

to dispense an ancient brand of justice the men of the new West had

believed long outdated.

For three straight years, Tom Horn patrolled the southern Wyoming pastures,

and how many men he killed after Lewis and Powell.

If he killed Lewis and Powell will never be known.

In 1898 with the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor, John Hay's

"splendid little war" broke out with Spain. Almost immediately Theodore Roosevelt

ordered a Brooks Brothers custom made uniform and

organized a volunteer cavalry troop of which he was to be second in command.

The troop was composed mostly of cowboys but also included a few

Indians and wealthy polo-playing easterners. Among those volunteering was

Tom Horn, who was assigned duty as a mule wrangler. After training in Texas, "Teddy's

Terrors" as the Rough Riders were sometimes known, arrived in Tampa, Florida, on

June 1, 1898.

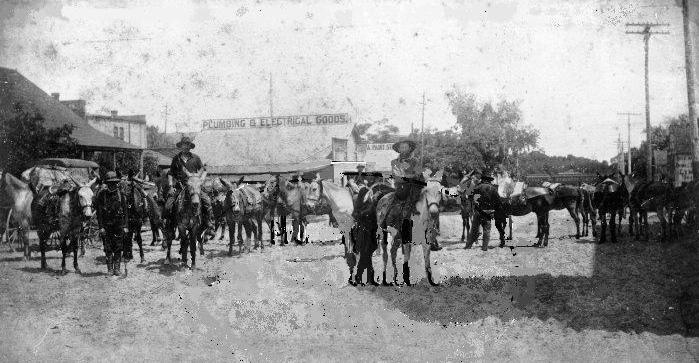

Rough Rider mules, Franklin Street, Tampa, Florida,

1898. Photo, courtesy Tampa-Hillsborough County Library System.

It is impossible to state with certainty that the

above photo shows Horn in Tampa. Names of the wranglers were obviously not taken down.

Conditions in Tampa were miserable. Camp Palmetto had to be abandoned because of

unhealthy conditions. The Rough Riders were assigned to Port Tampa where many

suffered from the tropical heat, humidity, and, after sundown or in the shade,

great swarms of mosquitoes. While the woolen uniforms may have helped provide

protection from the mosquitoes, they were of little help against the unrelenting heat.

Nor did they help against the chiggers which infested the grass and Spanish moss. The chiggers

would burrow beneath the skin at the cuff or belt line causing large red welts. The welts gave

rise to the local name for the insect, "red bugs." Horn never saw active duty

in Cuba. He was one of the many who came down with malaria in Tampa. Indeed, American

casualties in the splendid little war were 496 killed in action, 202 died from wounds, and

5,509 died from tropical deseases

Upon his return to Wyoming, Horn resumed his prior employment, ostensibly as a bronco

buster at $125.00 a month, for various ranches along the upper Chugwater.

Seven miles from Iron Mountain was the ranch of Kels Nickell, the only sheepherder

in the area. On July 18, 1901, Nickell's 14-year old son, Willie was shot and

killed by two bullets in the back. At the time Willie, tall for his age, was

wearing his father's coat and hat and was riding his father's favorite horse.

It is generally believed that the killer mistook Willie for Kels. Based upon blood at the scene, it was apparent

that Willie had fallen face down, and that someone had turned the body over and placed

a stone under Willie's head. The culprit left no footprints or shells at the

scene. Seventeen days later someone shot Kels, wounding him in the arm, hip,

and side. While Kels was in the hospital, masked men clubbed a number of Kels'

sheep to death. Shortly thereafter the Nickell family moved to Saratoga.

William "Willie" Nickell, 1901 William "Willie" Nickell, 1901

Victor Miller, a neighbor who was involved in a feud with Kels over the

sheep in cattle country,

was initially suspected of the crime. Ultimately

suspicion turned to Tom Horn because of Horn's involvement in prior killings. Deputy U. S. Marshal Joe LeFors invited Horn

to meet with him on the basis that he, LeFors, had a friend in Montana who needed

some "secret" work done by someone who was not known in the area. Specifically,

it was suggested that there was a "gang" which needed to be infiltrated. It was

proposed that someone was needed who would act as a "wolfer" and would be

accepted into the gang.

Horn met with LeFors in Cheyenne and the two engaged in conversation. Unbeknownst to

Horn, two witnesses were secreted in the next room: a short hand stenographer,

Charles Olnhaus, and Laramie County Deputy Sheriff, Leslie Snow. During the course

of conversations over two days, Horn allegedly admitted that he killed Nickell with his

Winchester Model 1894 30-30 rifle and placed a stone under Nickell's head as his "sign." Horn told

LeFors that he, Horn, had been paid in advance and received $2,100 for killing three men and taking

five shots at another. He told LeFors that the reason there were no

footprints is that he was barefoot. LeFors asked whether Horn had carried the shells

away, to which Horn responded: "You bet your [expletive deleted] life I did."

Additionally, Horn admitted to the unsolved murder of William Lewis and Fred Powell near Iron

Mountain in 1895.

Coble paid for Horn's defense, with Horn being represented by the general

counsel for the Union Pacific, John W. Lacey, formerly a Wyoming Supreme Court justice.

The exact employment relationship of Horn to the Iron Mountain spread

or to Coble is, however, uncertain. The ranch

foreman, Duncan Clark, testified after Willie Nickell was killed that Coble was east in

Pennsylvania at the time. Clark could not say whether Horn worked for

Coble because Horn "just comes in and goes out." In response to a direct question of

whether Clark knew where Horn came from when he rode in two days following the killing, he

responded: "No, sir, he never tells me and I never ask him.

I never expect to get the truth anyway." At the time Horn was riding a T Lazy Y horse,

a brand still in use in the Chugwater area.

Motion pictures have attempted to make it appear that there was considerable

doubt as to Horn's guilt. The films focused on the question of whether

Joe LeFors got Horn drunk and whether Horn had really confessed or if the shorthand stenographer

Charles Ohnhaus had misheard or mistranscribed Horn's statement.

The defense was three-fold: (1.)

Horn was under the influence of liquor, tended to make things up, and became talkative

when drunk. Witnesses were produced that Horn had been drinking. (2.) Horn had an alibi

and could not have been in the area at the time of

the killing. He was in Laramie City, as proven by the fact that Horn's horse, Pacer,

was lodged at a Livery in Laramie City for a ten-day period at the time of

the killing. Witnesses testified that Horn was nowhere near the Nickell Ranch at

the time of the slaying. (3.) The killing could not have occurred as he

described to LeFors in the following regards: (a.) Dr. Barber testified, based on learned texts, that

the wounds could not have been inflicted with a 30-30 similar to Horn's. (b.)

A witness was produced who had slept with Horn several days later and had observed

no injury to Horn's feet such as would have been produced had Horn gone barefoot. (c.)

Horn, in his statement to LeFors, described the shooting as coming from one direction.

The fatal shot came from another.

Horn Jury

Horn Jury

Horn took the stand in his own defense. In the final analysis it was Horn's

own testimony that hanged him. Horn admitted making the various statements testified to

by LeFors, Snow and Ohnhaus with

the exception of one statement which Horn did not remember but conceded he might

have made.

However, Horn contended that his

confession was a "josh;" it was merely

an exchange of wild tales. The witnesses admitted that although Horn had been

drinking, Horn was in control of himself. Dr. Barber admitted he could not say that

the wounds were not inflicted with a 30-30.

The alibi witnesses placed Horn in a different

location from that where Horn said he was. Other witnesses placed

Horn at the Miller Ranch 3 or 4 miles from the Nickell Ranch for several days before the

killing and at the William Clay Ranch just to the north of the Nickell spread. It was admitted that the time of check-in of Pacer at the livery in

Laramie City was filled out when Horn checked out. Horn could have made it to

Laramie City following the killing.

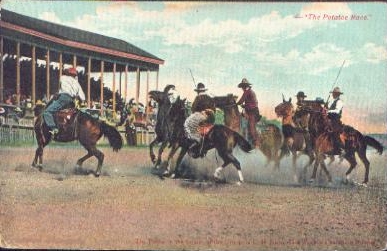

C. B. Irwin (in woolies) in Potato Race, Clearmont, 1904. See text below.

C. B. Irwin (in woolies) in Potato Race, Clearmont, 1904. See text below.

A jury of 11 whites and one black, Charles Tolson,

found Horn guilty on October 23, 1902, on the sixth ballot. At the end of the

fifth ballot, two jurors voted for acquittal.

The jury then examined all of the testimony. After re-examination, the two hold-out

jurors voted guilty. Each later made statements to the effect that

although they liked Horn, they had no choice but to find him guilty.

On appeal, Horn's lawyers argued, among other things, that the two hold-out jurors

may have been improperly influenced

by comments that they may have overheard while

dining. The head waiter of the hotel testified that guests of the hotel were

discussing the case when the jury was present. The two baliffs, who sat at either end

of the table in the hotel dining room when the jurors were served, testified that

they heard no improper comments from other diners in the hotel. Tolson, who sat

directly opposite the two jurors, testified

in similar fashion.

While awaiting the outcome of an appeal,

Horn spent his time braiding a rope, see photo above, and writing an autobiography.

His appeal was denied. He was hanged using his own rope

on November 20, 1903, while two friends, Charles B. Irwin and Frank Irwin, sang the hymn

"Life is Like a Mountain Railroad."

Tom Horn being placed in hearse. Charles Horn at right.

Tom Horn being placed in hearse. Charles Horn at right.

A new type of gallows was introduced for the execution using

an automatic trap activated by the weight of the convict, eliminating the

need for an executioner. This type of gallows remained in use until replaced

by the gas chamber. Horn's body was claimed by his brother Charles.

Horn was buried in Boulder, Colo. In 1914,

Coble, having seen his financial fortunes ebb, committed suicide in the lobby

of a hotel in Elko, Nevada.

Duncan Clark was killed in a hunting accident in April 1906 near Horse Creek

where he was then residing. His death has been used as the basis for various

conspiracy theories. Such theories include: (a) Willie Nickell was killed by Victor Miller using a gun

similar to Horn's Winchester so as to blame Horn; (b) Willie was killed by Jose

"Joe Good" Bueno, an outlaw from Brown's Hole, Colorado; and (c) the Wyoming Stock Growers Association conspired to "blow" the

defense and see Horn hanged rather than have him reveal their being involved in

the killings. A review of Justice Potter's opinion, Horn v. State, 12 Wyo. 80, 73 Pac. 705 (1903),

reflects that every argument in

Horn's favor was raised and carefully considered by the Wyoming Supreme Court. The

Horn case still cited as precedent in Wyoming courts. It is

extremely doubtful that a lawyer of John Lacey's reputation would join a conspiracy to

lose the case. Extraordinary efforts were made to save Horn including appeals to the governor for

clemency. Some, such as the unknown writer, excused Horn:

It is possible, although highly doubtful, that he killed none at all

but merely let his reputation work for him by privately claiming every

unsolved murder in the state.

It is also possible, but equally doubtful, that he actually shot down

the hundreds of men with which his legend credits him.

For that legend was growing explosively, Rumor was insisting he received

a price of $600 a man.

The best evidence is that he received a monthly wage of about $125, very good money in an era when top hands worked for $ 30 and board.

Rumor had it he slipped two small rocks under each victim's head as a sort of trademark

A detailed search of old coroner's reports fails to substantiate this in the slightest.

One thing was certain -- his method was effective, so effective that after

a time even the warning notices were often unnecessary.

The mere fact that the tall figure with the rifle and field glasses had been seen riding that way was enough to frighten three rustling homesteaders out of the Upper Laramie country in a single week

"My reputation's my stock in trade", Tom mentioned more than once.

He evidently couldn't foresee that it might be his downfall in the end.

He had made himself the personification of the Devil to the homesteaders.

But to the cattlemen who had been facing bankruptcy from rustling losses

and to the cowboys who had been faced with lay-offs a few years earlier,

he was becoming a vastly different type of legendary figure.

Such ranchers as Coble and Clay and the Bosler brothers carried him

on their books as a cowhand even while he was receiving a much larger

salary from parties unknown.

He made their spreads his headquarters, and he helped out in their roundups

In the cow camps, Tom Horn was regarded as a hero, as the same kind of

champion he was when he entered and invariably won the local rodeos.

The hands and their bosses saw him as a lone knight of the range,

waging a dedicated crusade against a lawless new society that was

threatening a beloved way of life.

The wailing , guitar-strumming minstrels of the cattle kingdom

made up songs about him.

By 1898, rustling losses had been driven down to the lowest level

ever seen in Wyoming.

Horn Grave, Columbia Cemetery, Boulder, Colo., photo by Geoff Dobson

In the final analysis, it must be said the jury was there, they heard the witnesses, and,

upon consideration of all the evidence, they found they had no other choice but to

find Horn guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Thus, the mystery of Tom Horn, the one he took to

his grave, is not if he killed Willie Nickell. Unanswered questions remain after 100 years: Who paid Horn the

$2,100; who paid Horn to kill Isom Dart, Matt Rash, William Lewis, and Fred Powell; and who actually

wrote Tom Horn's autobiography. Was it Horn, as claimed by Coble's widow, or Hattie

Horner Louthan, a sometimes newspaper correspondent and member of the staff of the

Denver Republican? And what of Glendolene Myrtle Kimmell, Horn's romantic interest as

portrayed in the movies? Miss Kimmell, who stuck by Horn to the end and who blamed

Victor Miller for the killing, never married. She allegedly wrote a manuscript,

The True Life of Tom Horn, portraying Horn as a knight errant caught between two

conflicting worlds. It was never published. What whould it have

revealed? Unfortunately we may never know for Miss Kimmell died at age 70 in Los Angeles, California, on

September 12, 1949. And who is the author of the fragment copied above found

at a Canadian university?

Directions to grave: From Broadway take College Avenue west to

cemetary. Next to cemetery on north side, street widens to permit parking. Grave is at 2:00 o'clock

position from first parking space, about 10 graves in.

Music on this Page: Life is Like a Mountain Railroad

by Eliza R. Snow and M.E. Abby

Life is Like a Mountain Railroad

Verse

Life is like a mountain railroad

With an engineer so brave

We must make this run successful

From the cradle to the grave

Watch the curves, the fills the tunnels

Never falter, never fail

Keep your hand upon the throttle

And your eye upon the rail

Refrain

Oh, blessed Savior, thou wilt guide us

Til we reach that blissful shore

Where the angels wait to join us

In God's grace forever more

Verse

As you roll across the trestle

Spanning Jordan's swelling tide

You behold the union depot

Into which your train will glide

There you'll meet the superintendent

God the Father, God the Son

With a hearty, joyous greeting

Weary pilgrim, welcome home

Refrain

|