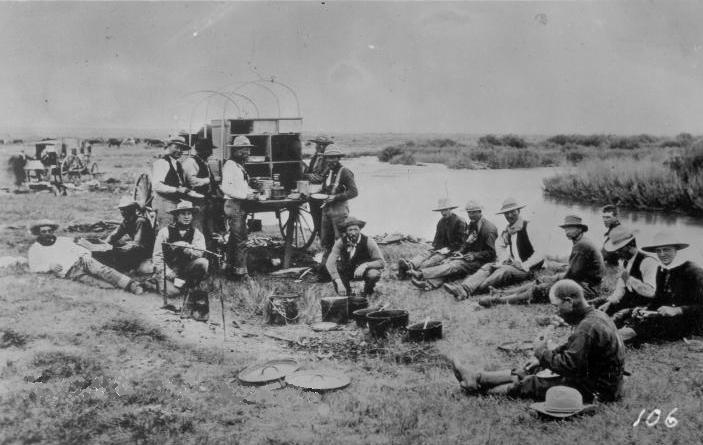

Roundup Camp, Wyoming, 1880's

The flat brimmed hats some of the

cowboys are wearing is the Stetson "Boss of the Plains" hat originated in 1865 and sold for $5.00. By

1900 it was sold by Sears Robuck and Company for $4.50 plus postage. Shaping of the brim and crown

was done by the owner. As noted with regard the discussion of Cheyenne, the

chuckwagon was invented by Charles Goodnight. Brands included Studebaker, South Bend, Owensburrow, McCormick-Deering and Weber. McCormick-Deering in

1907 changed its name to International Harvester and continued to supply wagons until the 1940's.

After 1936 all of the International wagons were manufactured by Keller Manufacturing Company which discontinued

production in 1943 and converted to the manufacture of furniture. Studebaker also built a heavier

wagon known as the "roundup wagon" more suited to roundups but not as well suited to

trail drives as the lighter

chuckwagon. On large drives an additional wagon known as a "hoodlum wagon" was

used for carrying bed rolls and personal gear.

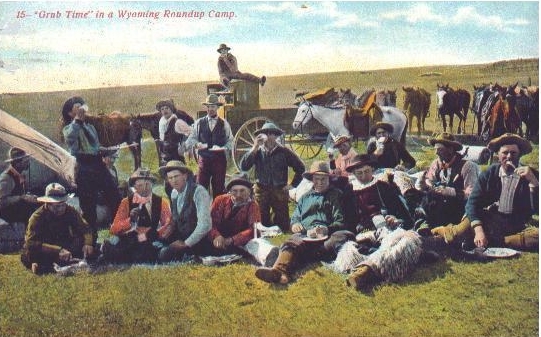

Roundup Camp, Warren Livestock Company, near Cheyenne, 1898, photo by Joseph Stimson. Another view of

same scene below right.

Frequently older photographs would be colorized at a later time for postcards.

Such is the above. For information as to J. E. Stimson see

Cheyenne III. The following commentary was written by the roundup foreman in the

photograph, Ashley Gleason, in 1921. Left to right:

"William Fry, photographer, northern New Mexico; L. T. Bennett, busily engaged

in cutting a tough beefsteak, Fort Duckane, Utah; Perry Williams, Cheyenne; Charles Phelps, Casper; Lon Roach,

now state law enforcement official; Roy Baxter, government pack master; Bob Van Horn, son of commanding

officer at Fort Russell; Dick Dummet, A.P.O. rep; was such a poor rep was sent home with his string, and

gladly were the neck tie horses gathered for him; Pete Anderson, didn't want to hide his face with a

cup, but his eagerness to get the sugar settlings, was caught in the act.

Pete was as good a day jingler as any, even though he was a Swede. He was

a physical wreck following the Spanish-American War; Joe Benjamine wanted to be sure

of getting in, so took to the top of the mess box; Guy McNurlen, a wonderful buster, he has fought many a wild bronk at Frontier

Days; Bill Hosack, Granite Canyon, Wyo., he is wearing among the first angora schaps introduced

into this country; Ed Clark, Virginia Dale, Wyo; Joe Detrick, has probably

attained greater wealth than any one of the bunch. He left riding because he

couldn't stick with them. He began mining and later accumulated much wealth; Ashley

L. Gleason, in 1921 was foreman for the Fiddleback Co., wool growers Douglas, Wyo;

George Johnson now in California."

Another view Warren Livestock Company Roundup Camp, 1898, photo by J. E. Stimson

Joe Benjamine is still on top of the mess box. The others

have shifted position somewhat.

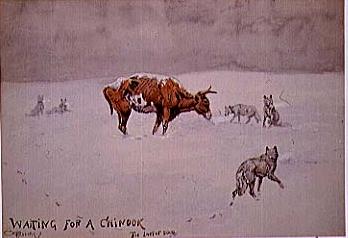

Although the editor of the Sheridan

City Directory, as noted on the Sheridan Page, may have believed that "in winter the

friendly 'chinook' wind mitigates the cold, killing winters of the Dakotas,"

as illustrated by C. M. Russell's famous sketch pictured below, chinooks are somewhat unreliable.

The winter of 1886-1887 was devasting to Wyoming's cattle industry. The giant British-owned Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited,

headquartered in Chugwater and Cheyenne, lost 50% of its calves and 15 to 20% of its entire stock. Other large companies

such as the Niobrara Land and Cattle

Company which had interests from Texas to Montana failed. In the instance of Swan fraud, as discussed below,

may also have contributed to large losses. On November 13, 1886, it started

to snow and continued for a month. In mid-December, however, there was a

thaw, turning the snow to slush. In late December the temperature turned to

the minus 30's turning the slush to a solid sheet of ice. January of 1887, was the coldest in memory and included one

72-hour blizzard. Teddy Blue Abbott, who received his nickname as a result of an

incident with a soiled dove in Miles City, Mt., noted:

"It was all so slow, plunging after them through the deep snow . . . .The horses' feet were cut and bleeding from the

heavy crust, the the cattle had the hair and hide wore off their legs to the knees and the hocks.

It was surely hell to see big four-year-old steers just able to stagger along. It was the same all

over Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado, western Nebraska, and western Kansas."

The effect was such that many eastern investors now withdrew and foreign ranchers simply left. T. Roosevelt noted:

"For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home. In its present

form, stock-raising on the plains is doomed and can hardly outlast the century."

"Waiting for a Chinook," C. M. Russell

In 1886 Charlie Russell was employed by Kaufman and Stadler. Kaufman wrote

asking how the cattle had fared. The response by Russell was a sketch of a

starving cow in the snow. Kaufman displayed the sketch in his office which led

to its popularity with requests of Russell for more copies. The version shown to the

left was painted about 1903.

Ranching in Wyoming started in the 1850's but received its real impetus as a result of the end of the Civil

War and the coming of the railroad. Cattle valued at $5.00 a head in Texas would bring ten fold that amount at

a railhead. Thus, there began the cattle drives to railheads in Kansas and to

Cheyenne.

A typical herd consisted of about 2,000 head with a trail

boss and a dozen men, although some herds of up to 15,000 were driven north with much bigger crews. Life on the trail was hard. One observed:

"They had very little grub and they usually run out of that and lived on straight beef, they had only three or four

horses to the man, mostly wth sore backs, . . .they had no tents, no tarps, and damn few slickers.

They never kicked, because those boys was raised under just the same conditions as there was

on the trail--corn meal and bacon for grub, dirt floors in the houses, and

no luxuries."

Actually, it was rare to get "straight beef" on the trail, particularly on drives

conducted by "contract drovers" who were driving cattle owned by someone else. On the trail

there was no way of preserving beef and, thus, the menu was limited to items which

would keep, i. e. beans, biscuits and coffee, or the occasional "slow elk," a cow belonging to

another outfit. In the latter instance everything was used, giving rise to a

trail delicacy, "S.O.B. stew," made of tallow, tongue, liver, sweet breads, brains, marrow gut, and

anything else except hoofs, horn and hide.

The danger of a stampede was always present. One of the cowboys who rode the Goodnight-Loving Trail, Edward C. "Teddy Blue" Abbott,

recalled:

"If. . .the cattle started running--you'd hear that low rumbling noise along the ground and the men on

herd wouldn't need to come in and tell you, you'd know--then you'd jump on your horse and get out there in the

lead, trying to head them and get them into a mill before they scattered to hell and

gone. It was riding at a dead run in the dark, with cut banks, and prairie dog holes all

around you, not knowing if the next jump would land you in a shallow grave"[Webmaster's personal note: My grandfather, at about age 12, reversed

Horace Greeley's admonition and went East after being caught in a stampede

near Pueblo.]

The Two Bar, Chugwater, 1912

(Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited)

The center building burned in 1918. For another view see Deadwood Stage page.

Modern view of headquarters building and interior of barn below. The manager's residence was originally

constructed by Thomas A. Maxwell about 1876. By the time of the above view it had been

added to several times. Maxwell's widow sold the home ranch to Swan Land & Cattle Co., in 1882.

Modern view of Swan Land & Cattle Company home ranch.

In the 1870's, stockgrowers discovered that cattle could winter over on the northern plains.

In the early 1880's speculative fever overtook the industry with investors in Britain and elsewhere

being promised a 20% return on investment. In November, 1882, Alexander Hamilton Swan (1831-1905), president of three

cattle companies, Swan & Frank Live-Stock Company, National Cattle Company, and the Swan, Frank & Anthony

Cattle Company, along with James Converse, Joseph Frank and Godfrey Syndacker, entered into a transaction with James Wilson of Edinburgh, Scotland, whereby there was sold

in March, 1883, for the sum of $2,553,825 to the Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited, a British

limited liability company:

"all and singular the lands and tenements, water rights, improvements upon lands, houses, barns, stables,

corrals, and other improvements and grazing privileges; also all live stock,

consisting of neat cattle, horses and mules, belonging to the said three Wyoming corporations, or any

or either of them; also all live stock, brands, tools, implements, wagons,

harness, ranch, camp, and round-up outfits, and branding irons"

Swan produced to the investors herd books, which he represented as being accurate, showing 89,167 cattle.

Swan, at a later time, was quoted as stating:

In our business we are often compelled to do certain things which, to the

inexperienced, seem a little crooked.

As a part of the transaction Swan was employed as general manager at a

salary of $10,000.00 a year, this at a time when highpaid cowboys would dream of working for the

"Two-Bar"

for $45.00 per month plus the promise of rice 'n raisin pudding for dessert. The following year, 1884, the Company purchased

from the Union Pacific 550,000 acres for $2,300,000, giving it control over

3.25 million acres. It owned so many brands that it had to publish a brand book so that

its foremen would be able to keep up with the Company's brands. The home ranch in

Chugwater was connected to Company headquarters in Cheyenne by a telephone

line that cost the Company 1,000 pounds sterling to install. Additionally, the company maintained

its own hotel in Cheyenne for personel visiting the headquarters.

Interior of

barn, Swan Home Ranch. Exterior, 1909 color view above.

Following the "Die off", the Company contended that the herd books had been

falsified, that the actual number of cattle was at least 30,000 less than represented and

the Company had been cheated out of more than $800,000. Needless to say, Swan was

fired and Scottish-born John Clay (1851-1934) became general manager. Clay is also noted as

having served as the President of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and managed other British-owned ranches. Swan had previous served also as president of the Association and was

also was instrumental in the formation of the Wyoming Hereford Association. Although Hereford had

previously been introduced to the other parts of the United States including Colorado, the

Association was responsible for introduction of Herefords to Wyoming at the

Kingman Ranch near Cheyenne. The Kingman Ranch is a predecessor of the

Wyoming Hereford Ranch on Campstool Road southeast of Cheyenne.

Chugwater Depot, 1913

Chugwater Depot, 1913

The Company sued Swan in a case going to the U.S. Supreme Court, but was

unable to collect. The Company was so large, however, that it had no choice

but to continue in business, slowly reducing its dependence on cattle and by 1909

had turned entirely to sheep. By 1917, the Company's finances had been completely

restored. In 1926, the Company was reorganized, in order to avoid British taxes,

as an American corporation organized under the laws of Deleware. In 1948,

the company's assets were liquidated with the last dividend of $1.55 a share

being paid in 1951.

Chugwater, named after Chugwater Creek, was

first settled in 1867 and rapidly became a center of the cattle industry.

Among the early ranchers along the Chugwater were the Clay brothers, William L. Clay

(1855-1939) and Charles Edward Clay (1838-1905) from Virginia. William L.

Clay originally married Lulu Fingernail Woman by whom he had four children. The

marriage ended in divorce pursuant to Indian custom, with Lulu Fingernail Woman

returning to her people leaving William to rear the children. He later

remarried. Charles Edward Clay served in Confederate forces during the Civil

War and later was elected to the Wyoming Legislature. The Clay name survives as the

name of a street in Chugwater.

In addition to being the headquarters of the Swan Land and Cattle Company,

Ltd., other ranches in the area included the Diamond Ranch, founded in 1880 by British

polo enthusiast George R. Rainsford, the Kelly Ranch, the Huff Ranch, and the Bosler Brothers.

The Bosler brothers, James Williamson Bosler, John Herman Bosler, and George Morris

Bosler, were originally from Pennsylvania and had ranching interests in both

Nebraska and Wyoming. Frank C. Bosler, son of John Herman Bosler, was a

partner of Alexander Swan in the Omaha stockyards and was a stockholder in

the Ogalalla Land and Cattle Co.

1st Street looking north, Chugwater, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

The two-story building to the left is the old hotel. Chugwater, unfortunately, is a town where the

main business section has been bypassed by the Interstate just a few blocks away. On the

day the photo was taken, the only sign of life was one lone cowboy who emerged from

a building next to the museum and disappeared. The museum, itself, was closed and the

drugstore across the street from the museum, where one may obtain a key, was not yet open.

The popular version of how Chugwater received its name is that the word "Chug" is an onomatopoeic version of

the sound of a bison hitting the ground from an Indian buffalo jump.

Next page Tom Horn.

|