|

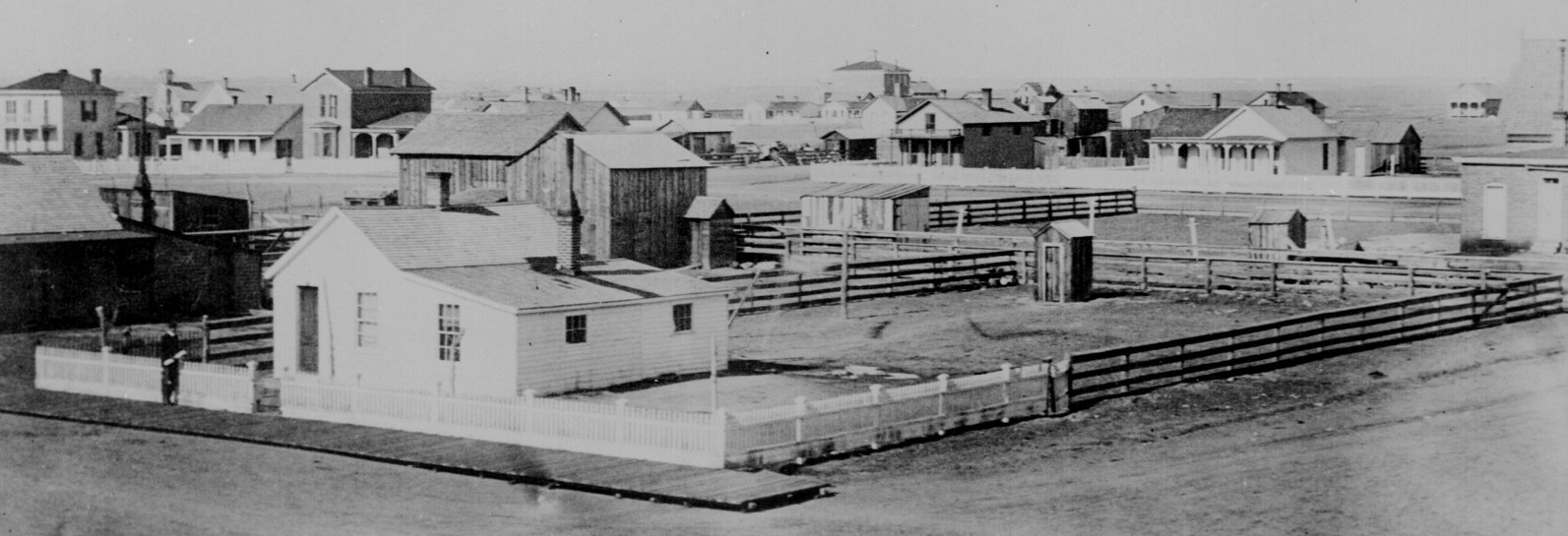

Cheyenne, 1876

Cheyenne, 1876

Compare with later images below on next page. Cheyenne began its growth with the arrival

of the Union Pacific Railroad in November 1867, the same year that the city was incorporated. Also in 1867, Denver merchant,

John Wesley Iliff, received a contract from the Railroad to provide beef for the railroad crews and

established a cow camp five miles down Crow Creek from Cheyenne. The following year Wells Fargo and Company established

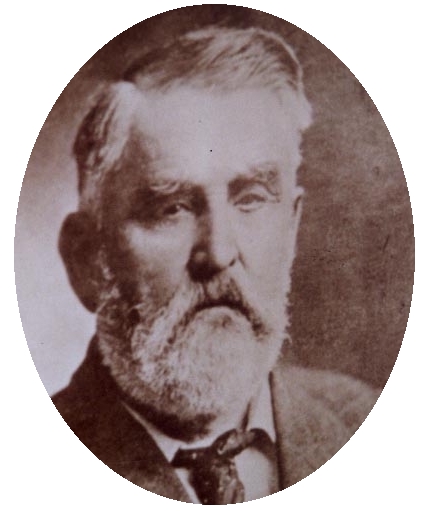

an agency. In 1869 Charles Goodnight (photo to right), in order to provide Iliff with the needed stock,

begain driving cattle to Cheyenne from Texas up what became known as

the

Goodnight-Loving Trail running from northwest of San Antonio, crossing the

Pecos at Horsehead Crossing and then into New Mexico. From

there it followed the Pecos until the trail turned north into

Colorado passing near present day Deer Trail. Railroad in November 1867, the same year that the city was incorporated. Also in 1867, Denver merchant,

John Wesley Iliff, received a contract from the Railroad to provide beef for the railroad crews and

established a cow camp five miles down Crow Creek from Cheyenne. The following year Wells Fargo and Company established

an agency. In 1869 Charles Goodnight (photo to right), in order to provide Iliff with the needed stock,

begain driving cattle to Cheyenne from Texas up what became known as

the

Goodnight-Loving Trail running from northwest of San Antonio, crossing the

Pecos at Horsehead Crossing and then into New Mexico. From

there it followed the Pecos until the trail turned north into

Colorado passing near present day Deer Trail.

In the first year Goodnight sold Iliff $40,000 worth of cattle and during

the period up to 1876 provided some 30,000 head of longhorn.

Goodnight is also noted for being the inventor of the chuckwagon.

In 1866 he bought a war surplus Studebaker army wagon, added a canvas cover, water barrel, tool box and nailed a

set of kitchen cabinets to the back. Studebakers were especially suitable since they

used steel axles and could take the rough ride over the trails. Eventually similar wagons were sold by

Studebaker Brothers for $75 to $100. For more on chuckwagons see Chugwater page.

One Texas historian, Dee Brown, has attributed the popularization of the term "cowboy"

to Goodnight's wife, Mollie, who referred to her husband's drovers as their "boys." The term, howver,

dates back to a least the American Revolution when it was used to describe Loyalist

rustlers in the Mid-Hudson Valley of New York. The most famous was Claudius

Smith who had a hideout in the Ramapo Mountains and would raid farms in Orange,

and Rockland Counties, New York and Bergen County, New Jersey. He was eventually captured and

hanged on January 22, 1779, at Goshen, New York. Rustlers who preyed on Loyalist farmers were known as "skinners."

Clay Allison

One of Goodnight's "boys" who helped lay out the Goodnight Trail was the

infamous self-styled "shootist" Robert Clay Allison. Allison after leaving Goodnight's employment, started

his own ranch in New Mexico in 1870. He could best be described as a belligerent drunk. The Confederate Surgeon

General's Department, in giving him an administrative discharge for medical reasons, described him as:

"incapable of performing the duties of a soldier because of a blow received

many years ago. Emotional or physical excitement produces

paroxysmals of a mixed character, partly epileptic and partly maniacal."

Allison reputedly killed 15 men. However, his reputation was initially made as a result of

his involvement in the lynching of Charles Kennedy. Kennedy, at the instigation of Allison, was

dragged out of a jail in New Mexico, taken to a local slaughter house and dispatched. He was

then decapitated by Allison, who impalled Kennedy's head on a pole, and carried it to Henry Lambert's

Saloon on the Cimarron for display. In another incident in Canadian, Texas,

Allison allegedly strode around town seeking a gunfight, clad only in boots, hat and

gunbelt with two revolvers. In Las Animas, Colo., Allison killed a deputy sheriff. Two other deputies

fled town. As a result of his reputation Allison found it increasingly difficult to

find a town where he was welcome to sell his cattle.

In 1886, Allison trailed a herd of cattle to Rock Creek. Suffering from a tooth ache, he

stopped off in Cheyenne on his return to New Mexico and sought out the services of a dentist. The dentist,

unfortunately, began drilling the wrong tooth. Allison left the dentist and had the

tooth corrected by another dentist. He then returned. Pinning the first dentist in his chair, Allison

commenced the forcible extraction of the dentist's teeth. Only the response of passersby to the screams

emitting from the dental office saved the dentist.

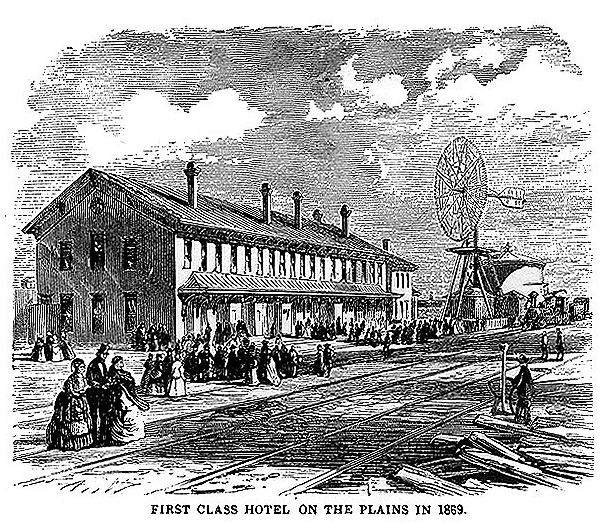

In 1869, Albert D. Richards, a correspondent for the New York Tribune, described

Cheyenne:

Cheyenne is the capital of Wyoming, the desert city of a desert State. It is watered by Crow Creek,

a little stream which feeds the Lodge Pole, and then the Platte. It boasts

a great locomotive-house of sand-stone; stone machine-shops just rising for

the Railway Company; a long, porticoed frame hotel [view below], also belonging to the

Union Pacific, which will dine four hundred people and lodge fifty; a few

large warehouses; three or four blocks of low, flat-roofed wooden shops,

full of goods; mainly scattering tents and shanties; two daily newspapers;

two churches; a score or two of drinking, gambling, and dance-houses, which

are crowded after dark; and a population of five thousand.

Union Pacific Hotel, Cheyenne, 1869, woodcut

Richards continued in his description:

For a wonder, it has neither an Opera House, nor an Academy of Music!

But I find instead the enormous tent of a traveling circus from the

"States." In the evening, it is crowded with twelve hundred people,

all eager for the "great moral spectacle," which some have come forty

miles on the railway to enjoy. There sat the tanned youth, eating molasses

candy, with their "girls," the boys yelling with delight at the little mule,

and everybody applauding the clowns’ time-honored jokes, in the good,

old-fashioned country way.

Cheyenne is woefully destitute of a "back country." It borrows leave to be

from the Denver trade, the railway machine-shops, and the new Sweetwater

gold mines, which, though two or three hundred miles to the north-west,

buy most of their supplies here. Lumber costs from $60 to $100 per 1,000;

wood, $8.75 per cord, and milk, twenty cents a quart. A few ranches are

opening; but Wyoming boasts of very little soil which promises to reward

the farmer—less than any other State or Territory. By way of compensation,

though, it has gold mines which are opening well, and some of the richest

coal fields in the world. The whole of it, too, is excellent grazing range;

the beef at the Cheyenne Hotel, wintered upon those mountain deserts, is

as rich and tender as I ever tasted at Delmonico's.

With territorial status Cheyenne was made the capital. With the railroad the

city became the jumping off location for freighters and miners heading north to the

Black Hills. In 1876 the Black Hills stage line was established. See discussion of the

Deadwood Stage. Thus, as illustrated in the next view

and the views on the next page, Cheyenne in its early days

was a tad "wild and woolly."

Cheyenne, 1877, woodcut, Leslie's Illustrated News

The above is a portion of a woodcut appearing in 1877 in Leslie's Illustrated News.

The balance of the picture appears on the next page. In the foreground is a freight

wagon and behind it the Cheyenne and Black Hills Express Stage, the famous

"Deadwood Stage," which ran from Cheyenne to Horse Creek, Fort Laramie, Rawhide Buttes,

Custer City and on into Deadwood.

Cheyenne Photos continued on next page.

|