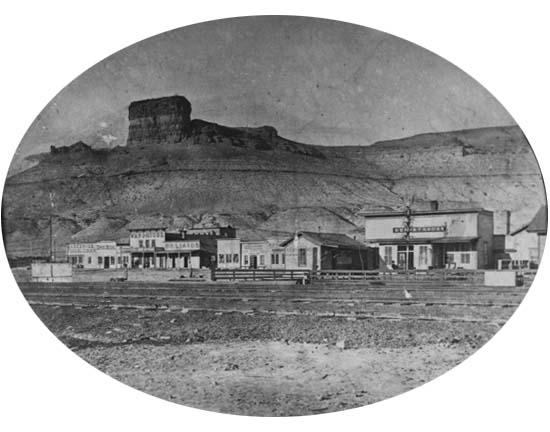

Green River City, 1876

Compare above photo with 1907 view below left. Green River City, now Green River, the third

place of the same name in Wyoming, was founded with the arrival of the

railroad in 1868 when the area was still a part of

Dakota Territory.

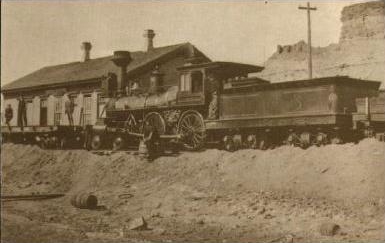

Engine No. 86, Green River City, 1869, photo by Wm. H. Jackson

Engine No. 86, Green River City, 1869, photo by Wm. H. Jackson

In 1869, William Henry Jackson undertook a photography

expedition along the Union Pacific. Jackson left Omaha and purchased a ticket to the

next town. There he would take photographs similar to those

that had earlier been taken by A. J. Russell, an

official photographer of the Railroad. When Jackson had raised enough money, he would

then purchase a ticket to the next stop, working his way along the line to

Salt Lake. The photo, above right, is of the same locomotive as that in a

stereopticon photo of Engine No. 86 which

had been taken the year before by A. J. Russell. Jackson's photography came to the

attention of F. V. Hayden, who recognized that photographic documentation of his

expeditions were vital to receiving further funding. Hayden offered the position of

photographer for his 1871 expedition to Jackson without pay. Jackson's photographs assured his

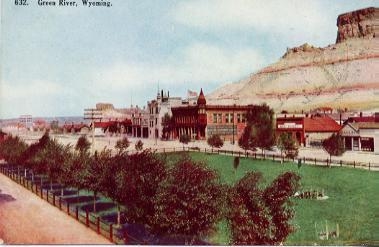

later success which included service on Hayden's later expeditions.  Green River, 1907

Green River, 1907

The first Green River was a stage station located about

34 miles north of the present city. The second was on the south side of

the river. For the first several years Green River City housed the temporary jail for Carter County (renamed Sweetwater

County in 1869),

although the county seat was in South Pass City 75 miles miles to the northeast. By 1870 South Pass City

had obtained its own jail but it was obvious that South Pass City was fading. By 1872 Green River City was showing growth with,

among other things, the Sweetwater Brewery. The following year,

1873 the county seat was moved from South Pass City. The City was

incorporated in 1891. Because of county line changes, South Pass City is now in Fremont County.

The corner building with the Queen Ann style projecting tower in the photo to the above left

housed the Morris Mercantile Co. Many of the photos on this web site were originally published

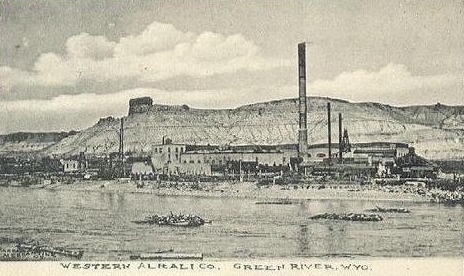

by local mercantile companies such as Morris. An example of one published by Morris

Mercantile is the photo of the Western Alkali Co., from about 1910, below right.

It was in Green River that Robert Leroy Parker, aka "George Cassidy," received the

nickname "Butch" while employed, 1885-1886, in Charles Crouse's butcher shop. According to one source,

Crouse would butcher rustled cattle from Brown's Park, Colo., where he also maintained

a ranch. Crouse (1851-1906) maintained a good relationship with the Wild Bunch although he was not an

actual member of the gang. Crouse's children themselves were a bit wild. In one instance

his two soms, Clarence and Stanley, drunk, rode into Linwood, Utah, stark naked, roped a local

blacksmith and part-time deputy sheriff and craps dealer, Pete Miller, and dragged Miller around town. Ultimately,

two locals rescued Miller. good relationship with the Wild Bunch although he was not an

actual member of the gang. Crouse's children themselves were a bit wild. In one instance

his two soms, Clarence and Stanley, drunk, rode into Linwood, Utah, stark naked, roped a local

blacksmith and part-time deputy sheriff and craps dealer, Pete Miller, and dragged Miller around town. Ultimately,

two locals rescued Miller.

One of the more famous guests of the Green River jail was the black rustler, Isom Dart (1855-1900). Dart was placed

in the jail on suspicion of murdering a Chinese cook who disappeared after winning several hundred dollars from

Dart in a fixed card game. Dart was housed in the same cell with a South Pass City miner, Jessie Ewing.

Ewing was sometimes referred to as the "ugliest man in South Pass City" because of a

badly disfigured face arising out of an

unfortunate meeting with a grizzly. During the night, Ewing beat Dart into submission.

The next morning, when breakfast was served, Ewing required Dart to get down on his hands and

knees so that Ewing could use Dart's back as a table, there being none in the cell. Ultimately, the Chinaman turned up and

Dart was released. Dart was shot and killed by Tom Horn on Oct. 3, 1900, in

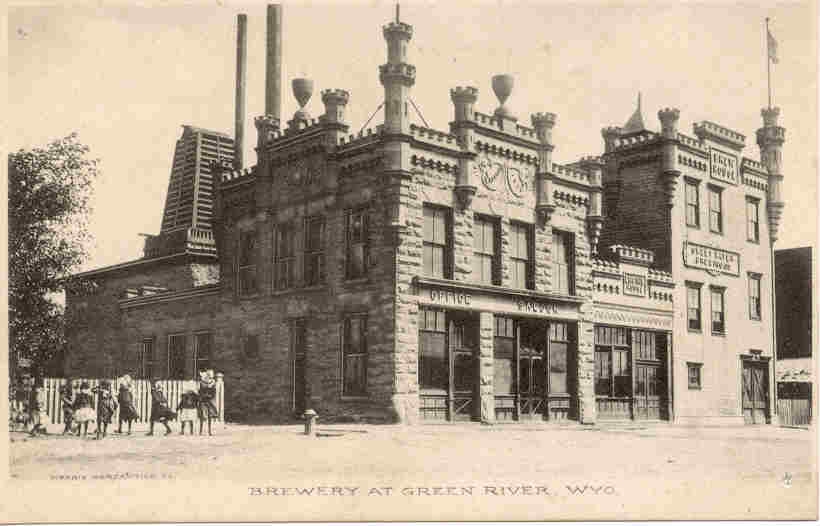

Brown's Park, Colo.  Sweetwater Brewery, Green River, undated

Sweetwater Brewery, Green River, undated

Granger Stage Station, 1860's Granger Stage Station, 1860's

Compare the photo to the left, taken when the stage station was in

use, with the more modern photo below.

In 1862 Ben Holladay moved stage and mail service from the Oregon Trail to the

Overland Trail in the general vicinity of the Cherokee Trail. the increased traffic required that the station at

the confluence of Ham's Fork and Black's Fork be upgraded and, accordingly,

a new station, pictured above was constructed about four miles from the old one. Wm. H. Jackson, before joining his brother to form

Jackson Brothers Studios in Omaha, worked as a bullwhacker on the road and in 1932 recalled spending three weeks at the station

in 1866. In 1866 the line was sold to Wells Fargo and Company but was closed down in 1869 with the

opening of the railroad.

Eugene Ware, who served in the military in Nebraska and what was to become Wyoming, described in his

memoir, The Indian War of 1864, the stage operation:

The stage stations were about ten miles apart, sometimes a little more and

sometimes a little less, according to the location of the ranches. Stores

of shelled corn, for the use of the stage horses, were kept at principal

stations along the line of the route. Intermediate stations between these

principal stations were called "swing stations," where the horses were

changed. For instance, the horses of a stage going up were taken off at

a swing station, and fed; they might be there an hour or six hours;

they might be put upon another stage in the same direction, or upon

a stage returning. It was the policy of the stage company to make the

business as profitable as possible, so it did not run its coaches until

each coach had a good load, and they were most generally crowded with

persons both on the inside and on top. Sometimes a stage would be almost

loaded with women. From time to time stage company wagons went by loaded

with shelled corn for distribution as needed at the swing stations. All

of the coaches carried Government mail in greater or less quantities.

Occasionally when the mail accumulated, a covered wagon loaded with mail

went along with the coaches. These coaches were billed to go a hundred

miles a day going west; sometimes they went faster. Coming east the

down-grade of a few feet per mile enabled them to make better time.

They went night and day, and a jollier lot of people could scarcely

be found anywhere than the parties in these coaches.

Overland Coach, 1869, soldiers on top

The coaches were all built alike, upon a standard pattern called

the "Concord Coach," with heavy leather springs, and they drove from

four to six horses according to their load. The drivers sat up in the

box, proud as brigadier-generals, and they were as tough, hardy and

brave a lot of people as could be found anywhere. As a rule they were

courteous to the passengers, and careful of their horses. They made

runs of about a hundred miles and back. I got acquainted with many

of them, and a more fearless and companionable lot of men I never met.

There seemed to be an idea among them that while on the box they should

not drink liquor, but when they got off they had stories to tell, and

generally indulged freely. They gathered up mail from the ranches, and

trains, and travelers along the road, and saw that it reached its

destination. They had but very few perquisites, but among others was

the getting furs, principally beaver-skins, and selling them to passengers.

Most of them had beaver-skin overcoats with large turned-up collars.

We soon understood the benefits of these collars, and the officers of our

post put large beaver collars on their overcoats, and the men of the

company fitted themselves out with tanned wolfskin collars, which were

equally as good. Wolves were so numerous that there was quite an

industry in shooting or poisoning them, and tanning their skins for

the pilgrim trade.

The accomodations at the various stage stations maintained by Holliday received mixed reviews. Sir Richard Burton

on his 1860 stage trip across the west, reported of the original Green River station:

"The station had the indescribable scent of a Hindu village,

which appears to be the result from burning of bois de vache and a few cows

which were so lively it was impossible to milk them. We supped comfortably on

salmon, trout, buffalo-berry jelly and ‘Valley Tan’ whiskey."

Sir Richard Burton August 21, 1860 6:30 PM. [Webmaster's note: bois de vache, cow chips.]

Modern view of Granger Station, on Old U.S. 30. Photo courtesy of

Library of CongressSir Richard gave a far less complementary review of the orignial station at

Ham's Fork:

The station was kept by an Irishman and Scotsman "David Lewis". It was a

disgrace. The squalor and filth were worse almost than the two -- Cold Springs

and Rock Creek -- which had called our horrors, and which had always seemed to be the

ne plus ultra of Western discomfort. The shanty was made of dry stone piled up against a dwarf

cliff to save backwall and ignored doors and windows.

Samuel Clemens in Roughing It described the accommodations and napery furnished to

passengers of the stage line:

The station buildings were long, low huts, made of sundried,

mud-colored bricks, laid up without mortar (adobes, the Spaniards

call these bricks, and Americans shorten it to 'dobies). The roofs,

which had no slant to them worth speaking of, were thatched and then

sodded or covered with a thick layer of earth, and from this sprung

a pretty rank growth of weeds and grass. It was the first time we had

ever seen a man's front yard on top of his house. The building consisted

of barns, stable-room for twelve or fifteen horses, and a hut for an

eating-room for passengers. This latter had bunks in it for the

station-keeper and a hostler or two. You could rest your elbow on

its eaves, and you had to bend in order to get in at the door.

In place of a window there was a square hole about large enough

for a man to crawl through, but this had no glass in it. There was

no flooring, but the ground was packed hard. There was no stove,

but the fire-place served all needful purposes.

Clemens continues:

There were no shelves, no cupboards, no closets. In a corner stood an open

sack of flour, and nestling against its base were a couple of black

and venerable tin coffee-pots, a tin teapot, a little bag of salt,

and a side of bacon.

By the door of the station-keeper's den, outside, was a tin wash-basin,

on the ground. Near it was a pail of water and a piece of yellow bar soap,

and from the eaves hung a hoary blue woolen shirt, significantly -- but

this latter was the station-keeper's private towel, and only two persons

in all the party might venture to use it -- the stage-driver and the

conductor. The latter would not, from a sense of decency; the former

would not, because did not choose to encourage the advances of a

station-keeper. We had towels -- in the valise; they might as well

have been in Sodom and Gomorrah. We (and the conductor) used our

handkerchiefs, and the driver his pantaloons and sleeves. By the door,

inside, was fastened a small old-fashioned looking-glass frame, with

two little fragments of the original mirror lodged down in one corner

of it. This arrangement afforded a pleasant double-barreled portrait

of you when you looked into it, with one half of your head set up a

couple of inches above the other half. From the glass frame hung the

half of a comb by a string -- but if I had to describe that patriarch

or die, I believe I would order some sample coffins.

Holliday's personal accommodations were, however, better. Eugene Ware described Holliday's

personal coach:

The coach was a sort of Pullman conveyance. They had a mattress on the

floor of the coach, and they slept in the coach, and when they rode,

they rode with the driver, and on a seat on the top. They had another

coach, in which there were servants, a cook, and supplies. Each

of these coaches was drawn by six horses, and went as fast as the fastest.

Ferdinand V. Hayden, 1871, Wm. H. Jackson

Ferdinand V. Hayden, 1871, Wm. H. Jackson

The 1871 expedition was not Hayden's first trip into Wyoming. Hayden was a part of a scientific contingent under

Gouverneur Kemble Warren in the military expedition into the Yellowstone and Powder River Country under the command of

then Col. Wm. S. Harney. The expedition was intended to punish the Sioux for the massacre of Lt. John L. Grattan and his Company. Grattan was attempting

to punish Indians for the butchering of a cow near Ft. Laramie. Harney, with a force of 600 men, came upon

the camp of Chief Little Thunder near what is now Lewellyn, Neb. When the Indians began to flee, Haney deceived Little Thunder

with a white flag of truce, then surrounded the camp, killing men, women and children. Warren reported:

"The sight . . . was heart-rending--wounded women and children crying and moaning, horribly mangled by the bullets." Two dead women

were found clutching their dead children. Thus ended the Battle of Blue Water Creek. Hayden was by professional training a surgeon. His only practice, howver,

was during the Civil War for the Union Army. By avocation he was a geologist. |