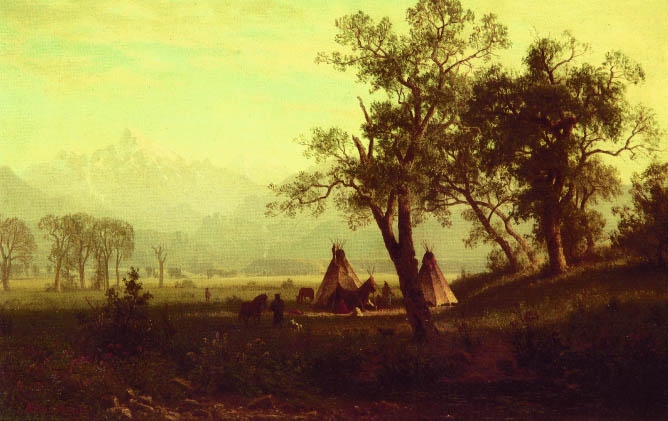

Wind River, 1860, Albert Bierstadt

South Pass from Wind River Mountains, 1860, Francis Seth Frost, below left.

As noted with regard to the discussion of Fort  Bridger, Frederick W. Lander's expedition of

1859 was responsible for the construction of the Lander Cutoff to Soda Springs, Idaho.

The expedition, however, also had the impact of romanticizing a view of the American West.

Included within the expedition were Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Francis Seth Frost (1825-1902). The two

spent five months, three weeks of which were in the Wind River Basin, with the

expedition making sketches and taking stereoscopic photographs. Three of Bierstadt's

sketches appeared in Harper's Weekly.

Upon their return to Boston they each produced epic paintings of the west, utilizing

the sketches and photographs. Bierstadt became one of the leading artists of the

late 19th Century and returned several times to the West including California and

Oregon, with his most famous paintings being of Yosemite. Frost's career as an artist, however, failed to

materialize and he remained primarily an art dealer. The Smithsonian Inventory of

American Paintings only lists seven examples of his work. Bridger, Frederick W. Lander's expedition of

1859 was responsible for the construction of the Lander Cutoff to Soda Springs, Idaho.

The expedition, however, also had the impact of romanticizing a view of the American West.

Included within the expedition were Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Francis Seth Frost (1825-1902). The two

spent five months, three weeks of which were in the Wind River Basin, with the

expedition making sketches and taking stereoscopic photographs. Three of Bierstadt's

sketches appeared in Harper's Weekly.

Upon their return to Boston they each produced epic paintings of the west, utilizing

the sketches and photographs. Bierstadt became one of the leading artists of the

late 19th Century and returned several times to the West including California and

Oregon, with his most famous paintings being of Yosemite. Frost's career as an artist, however, failed to

materialize and he remained primarily an art dealer. The Smithsonian Inventory of

American Paintings only lists seven examples of his work.

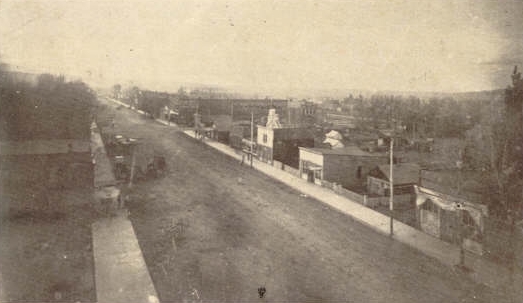

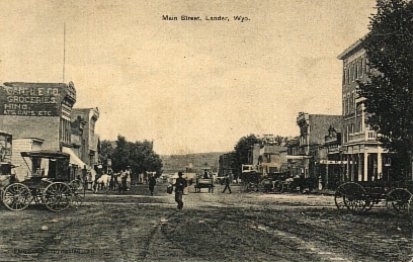

Lander, Wyo., 1910

Although settlement near Lander did not began until 1869 with

the establishment of Camp Augur, apparently named after Brevet Major

General Christopher C. Augur, many of the early expeditions passed through the

Wind River area. In 1856 Ramsay Crooks, one of the original Astorians,

described in a letter to the Detroit Free Press an

expedition through South Pass:

Mr. David Stuart sailed from this port [New York] in 1810

for the Columbia River on board the ship 'Tonquin' with a number of Mr.

Astor's associates in the 'Pacific Fur Company,' and after the breaking

up of the company in 1814, he returned through the Northwest Company's

territories to Montreal, far to the north of the 'South Pass,' which

he never saw.

In 1811, the overland party of Mr. Astor's expedition, under the command

of Mr. Wilson P. Hunt, of Trenton, New Jersey, although numbering sixty

well armed men, found the Indians so very troublesome in the country of

the Yellowstone River, that the party of seven persons who left Astoria

toward the end of June, 1812, considering it dangerous to pass again by

the route of 1811, turned toward the southeast as soon as they had crossed

the main chain of the Rocky Mountains, and, after several days' journey,

came through the celebrated 'South Pass' in the month of November, 1812.

Pursuing from thence an easterly course, they fell upon the River Platte

of the Missouri, where they passed the winter and reached St. Louis in

April, 1813.

The seven persons forming the party were Robert McClelland of Hagerstown,

who, with the celebrated Captain Wells, was captain of spies under General

Wayne in his famous Indian campaign, Joseph Miller of Baltimore, for several

years an officer of the U. S. army, Robert Stuart, a citizen of Detroit,

Benjamin Jones, of Missouri, who acted as huntsman of the party, Francois

LeClaire, a halfbreed, and Adré Valée, a Canadian voyageur, and Ramsay

Crooks, who is the only survivor of this small band of adventurers.

I am very sincerely yours,

RAMSEY CROOKS.

The Rendezvous of 1829 was held near present day Lander.

Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville's expedition of 1833 discovered an oil spring

in the Wind River Basin and was the first to take wagons through South Pass. Ostensibly

Bonneville's expedition was private. In reality it was at the behest of the

government and was for the purpose of spying on the British who were active

in the Pacific Northwest. The first oil well, Murphy #1, in the Territory was drilled in

Lander at Dallas Field, southeast of Lander, in 1883 by Mike Murphy. The field is still in production.

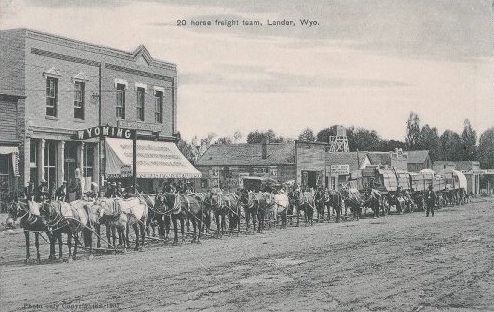

Twenty-horse freight team, Lander, 1906

The building is the Wyoming Saloon which featured the

first electrically lighted sign in the area. The building next to the sheep wagon at

the end of the train is Wah Lee's Chinese Laundry and Bath.

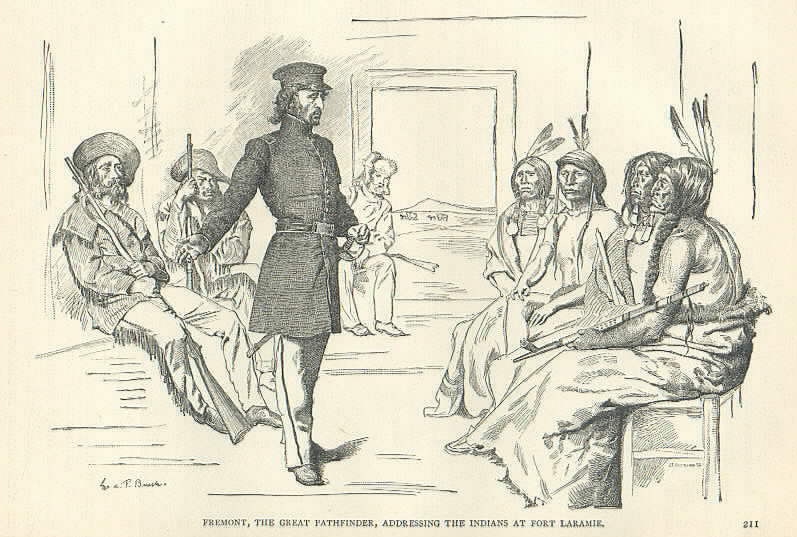

John C. Fremont's first two expeditions passed through the area. The first

expedition of 1842 made it as far as the Wind River Mountains and South Pass.

The second in 1843 demonstrated that South Pass was the best route through the

Rockies. Fremont on his various expeditions relied primarily on French trappers, including

Basil Cimineau LaJeunesse from Louisiana, as guides. The Seminoe Mountains and cutoff, as discussed with regard

to Ghost Towns, are named after LaJeunesse. as the Wind River Mountains and South Pass.

The second in 1843 demonstrated that South Pass was the best route through the

Rockies. Fremont on his various expeditions relied primarily on French trappers, including

Basil Cimineau LaJeunesse from Louisiana, as guides. The Seminoe Mountains and cutoff, as discussed with regard

to Ghost Towns, are named after LaJeunesse.

Fremont addressing the Indians at Fort Laramie.

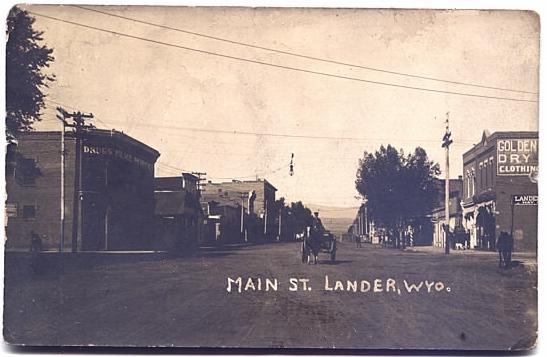

Lander, 1907, below left. Fremont Hotel at right in

photo.

Others on the Fremont Expeditions included

Kit Carson, Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell, Fremont's chief hunter, and Fremont's mapper, a German named Charles Pruess.

Maxwell

later went on to own approximately 2,000,000 acres in northern New Mexico. Billy the Kid

died in a house that had formerly belonged to Maxwell.

Fremont forebade the keeping of any journal other than that kept by Fremont himself. Insofar as

most of the men were concerned, this was a needless order since most, such as Carson, were

illiterate. Apparently unknownst to Fremont, Pruess secretly kept a diary in German which

has only come to light in the early 1970's. The journal, although showing that

Pruess regarded Fremont as a friend, also at times questioned his intelligence.

Pruess was also persnickety and insisted, unlike other members of the company, on

wearing clean clothes. Indeed, this was something which was highly unusual. One of the more

distinctive [pardon the pun] attributes of the early mountain men was their aroma.

As noted by Jim Clyman in Journal of a Mountain Man, the early trappers not only refused to change their clothes but would

wipe their knives and hands on their clothes after eating or after skinning animals: The journal, although showing that

Pruess regarded Fremont as a friend, also at times questioned his intelligence.

Pruess was also persnickety and insisted, unlike other members of the company, on

wearing clean clothes. Indeed, this was something which was highly unusual. One of the more

distinctive [pardon the pun] attributes of the early mountain men was their aroma.

As noted by Jim Clyman in Journal of a Mountain Man, the early trappers not only refused to change their clothes but would

wipe their knives and hands on their clothes after eating or after skinning animals:

"...Naturally, if some of this mixture (speaking of castorium) spilled on

their hands, they wiped it on their buckskins; they didn't stop there, but

wiped their greasy hands on their skins after eating, and wiped off the

blood when skinning. The resulting color and flavor of the skin was not

the clean gold of fresh-tanned hides, but, as Berry says....black. Dirty

black, greasy black, shiny black, bloody black, stinky black. Black."

[Webmaster's note: Castorium, an odoriferous oily secretion of the beaver, used in the making

of perfume.]

Some of the early mountain men never did get used to modern hygene. Jim Baker, who

also served in the Fremont Expeditions, ultimately settled down in a two-story log

blockhouse at Savery. In 1895 he and John Albert, another early mountain man, were

invited to serve as marshals for Denver's very first Festival of Mountain and

Plain. The committee put him up in one of Denver's finest hotels. When it was

suggested he might like to take a bath, he informed them he did not need one -- he had one this

year. Additionally, he refused to sleep in the bed, preferring the floor, and

refused to use the flush toilet, preferring the alley behind the hotel.

Lander, approx. 1907

Note the Golden Rule Store, predecessor of today's J. C. Penney Company,

to the right. For more on J. C. Penney see Kemmerer.

There was a value or purpose, however, to wiping the grease and other substances on the clothing.

David Lavender in Bent's Fort described the trapper's clothing:

"Down to his shoulders hung the hunter's hair, covered with a felt hat

or perhaps the hood of a capote. He liked wool clothing, for it would

not shrink as it dried and wake him, when he dozed beside the fire, by

agonizingly squeezing his limbs. But wool soon wore out and he then clad

himself in leather, burdensomely heavy to wear, fringed on the seams with

the familiar thongs which were partly to decorate but most utilitarian, to

let rain drip off the garment rather than soak in, and to furnish material

for mending. Further waterproofing was added by wiping butcher and eating

knifes on the garments until they were black and shiny with grease. Upper

garments might be pull-over type or cut like a coat, the buttonless edges

folded over and clinched into place with a belt. No underclothes were worn,

just breechclout. In extreme cold a Hudson's Bay blanket or a buffulo robe

was draped Indian-wise over the entire costume."

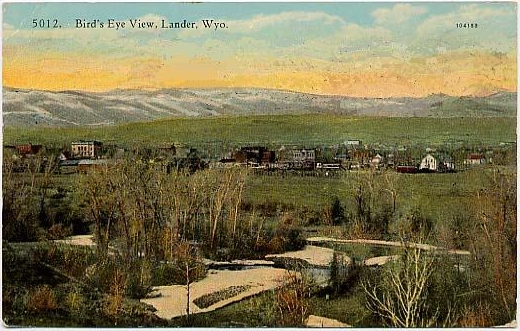

Lander, Wyo., 1929

Lander Photos continued on next page.

|