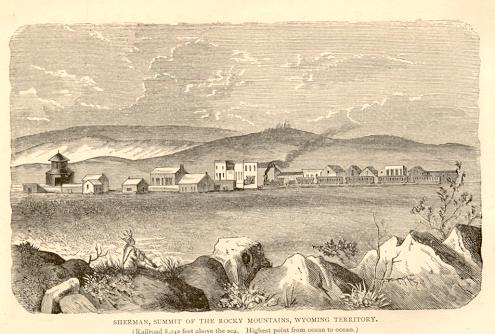

Sherman, Wyoming Terr., 1874

The coming of the railroad had a drastic impact upon Wyoming. As the Railroad progressed across

the Territory small towns and cities sprang up at the railhead to serve the

needs of the Railroad, the graders and others drawn to the area. Such was

Sherman, seventeen miles east of

Laramie and located at the highest point on the Railroad between the two coasts, 8,262 ft. above sea level.

at the railhead to serve the

needs of the Railroad, the graders and others drawn to the area. Such was

Sherman, seventeen miles east of

Laramie and located at the highest point on the Railroad between the two coasts, 8,262 ft. above sea level.

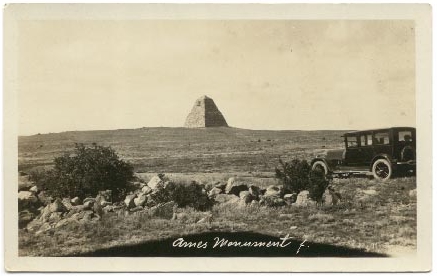

Ames Monument, Sherman, Wyo., photo by

Henning SvensonFor discussion of Henning

Svenson, see Laramie II.

Within 15 months of the railroad reaching Sherman Hill, the town boasted railroad

machine shops, a Wells Fargo express office, a newspaper, a millinery store and 2 two-story hotels,

the Sherman House and the Summit House. They were not

much as hotels but featured decent meals. Next door to the hotels was

a bar. Today, the existence of the town is marked only by the Ames Monument, pictured

above left and below, constructed by the Union Pacific in 1882; the foundation stones for

the railroad's windmill; and the cemetery. See photos of windmill foundation and

cemetery below.

Ames Monument, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

When the writer arrived at the above scene for the purpose of taking

some photos, an individual from the blue minivan was relieving himself on the

monument. Perhaps, but not likely, he was expressing his opinion from an historical perspective of the Ames

Brothers in whose honor the monument was erected. Indeed,

in an historical context one might not feel too kindly of Oliver Ames, Jr. (1807-1877) and

Oakes Ames (1804-1873). The two were at the very center of one of the greatest financial scandals in the

history of the American body politic, a scandal which implicated in allegations of

bribery the Vice President of the United States Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the

House of Representatives James G. Blain, the Republican candidate for vice president Henry Wilson, and

a future president of the United States James A. Garfield, as well as numerous

congressmen.

Bas-Relief by August Saint-Gaudens, Ames Monument, photo by Geoff Dobson

In the 1860's the attention of Oakes Ames, a congressman from Massachusetts, and

his brother was drawn to the Union Pacific and the generous subsidies it was receiving

from Congress. The two, having made a fortune in the management of their

father's shovel works which boasted of an average yearly production of over 1,400,000

shovels a year, acquired control over the Union Pacific. As a part of their scheme

to take advantage of the government subsidies, they also acquired control of a

Pennsylvania corporation which they renamed Credit Mobilier. The Union Pacific then

contracted with Credit Mobilier to construct 667 miles of the railroad. The actual

cost to Credit Mobilier was $44,000,000. The contract, using government subsidized funding, was for more than

$94,000,000. In order to preclude Congressional investigation, a large block of

Credit Mobilier stock held by Congressman Ames as trustee was ostensibly "sold" to

influential congressmen for one-third of its actual value. However, the "sale"

did not require actual money. The sales price was paid from the dividends resulting

from the profits on the railroad construction. Ultimately, the scandal was revealed by

the New York Sun. Although no one was indicted, Congressman Ames was censured by

Congress and died several months later, his reputation ruined. The Union Pacific was left heavily in debt.

The monument, itself, was designed by Henry Hobson Richardson, who was also the architect for

the Marshal Field's Store in Chicago. It has been contended that Richardson in his design

was inspired by the philosophy of Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of

New York's Central Park. Indeed, at the time the monument was under construction Olmstead wrote a

member of the Ames Family that it "was customary to commemorate important events by a form of monument * * * *

by bringing together at a place agreed

upon a great quantity of loose field stones and laying them up in the

conical pile known as a cairn."

The bas-reliefs of the Ames Brothers on either side

of the monument were sculpted by August Saint-Gaudens, famous as the designer of the

$20.00 gold piece.

Sherman, 2001, looking west, photo by Geoff Dobson

The town site of Sherman is located 1/4 mile west of the monument and is depicted in the

above photo. In the center of the photo,

running from left to right, is the former

railroad right-of-way. Toward the left of center may be made out the town site. To the

right of center a trail meanders up the hill to the cemetery. running from left to right, is the former

railroad right-of-way. Toward the left of center may be made out the town site. To the

right of center a trail meanders up the hill to the cemetery.

Foundation stones railroad yard, photo by Geoff Dobson

Sherman had as a part of the railroad yards a windmill

the vanes of which had a diameter of 20 feet.

It was used to pump water into a tank holding 50,000 gallons. For a photo of

a similar windmill at Laramie see Photos V.

Additionally, the yard had a roundhouse with five stalls and a turntable. The railroad shops

were required, in great part, by the necessity of double-heading the locomotives up

the steep grade from Laramie. Even today in wintertime the grade on the Interstate out of

Laramie can be an adventure.

In 1901, with the

construction of the Dale Creek embankment, the railroad

tracks were moved several miles away. Today, as indicated by the

above photos, little remains except pottery shards and rusted tin cans. Some artifacts,

however, are newer. On the day that the above photo was taken, a faded Pepsi

can bearing the 1984 football schedule for the Wyoming Cowboys was found. As all

historical artifacts should be, it was left in place.

Child's grave Sherman Cemetery, photo by Geoff Dobson

Child's grave Sherman Cemetery, photo by Geoff Dobson

With the abandonment of the town, many of the remains were removed by relatives to

cemeteries elsewhere. The photo is of the grave of a one-year old child who

died in 1888. Today, on the lonely, windswept knoll a 1/4 mile west of Sherman,

Mother Nature provides the flowers.

Directions to Sherman. Exit I-80 at Vedauwoo Road, approximately 16 miles east of

Laramie. Follow signs on graded road on south side of Interstate to Ames Monument. Last portion is on

unimproved road. Town site is approximately 1/4 mile west of monument.

More ghost towns on next page.

|