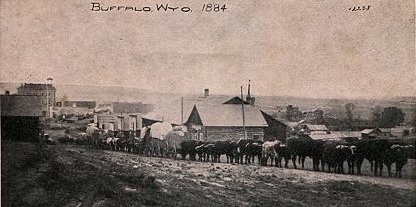

The Occidental, Buffalo, prior to 1895, near which the Virginian killed Trampas.

Before the gentle reader complains that the above photo looks nothing like the Occidental Hotel in Buffalo,

it

should be noted that Owen Wister's The Virginian, Horseman of the Plains ends

in 1889 with the

Virginian becoming a partner in the ranch. The original

Occidental, constructed by Charles Buel in 1880, was, as depicted, a log structure, large portions of

which floated down Clear Creek in the floods of 1895 and 1912, see photo of Occidental after the flood of

June 11, 1912, to the left. The present brick and

morter hotel (now a museum) takes up the entire block and dates to additions built in 1903, 1908 and 1910, long

after the Bishop of Wyoming was unsuccessful

in his efforts to dissaude the Virginian from accepting Trampas' challange. The Hotel

claims to have had Wm. F. Cody, Theodore Roosevelt, Owen Wister, Wm. T. Sherman and Calamity Jane as guests.

Our present day view of the West of the 1880's has, perhaps, been most influenced by

Roosevelt and Wister whose books and articles were illustrated by their mutual friend Frederic

Remington. Remington, in fact, in his 20's worked as a cowboy in the west before returning to

his native New York. it

should be noted that Owen Wister's The Virginian, Horseman of the Plains ends

in 1889 with the

Virginian becoming a partner in the ranch. The original

Occidental, constructed by Charles Buel in 1880, was, as depicted, a log structure, large portions of

which floated down Clear Creek in the floods of 1895 and 1912, see photo of Occidental after the flood of

June 11, 1912, to the left. The present brick and

morter hotel (now a museum) takes up the entire block and dates to additions built in 1903, 1908 and 1910, long

after the Bishop of Wyoming was unsuccessful

in his efforts to dissaude the Virginian from accepting Trampas' challange. The Hotel

claims to have had Wm. F. Cody, Theodore Roosevelt, Owen Wister, Wm. T. Sherman and Calamity Jane as guests.

Our present day view of the West of the 1880's has, perhaps, been most influenced by

Roosevelt and Wister whose books and articles were illustrated by their mutual friend Frederic

Remington. Remington, in fact, in his 20's worked as a cowboy in the west before returning to

his native New York.

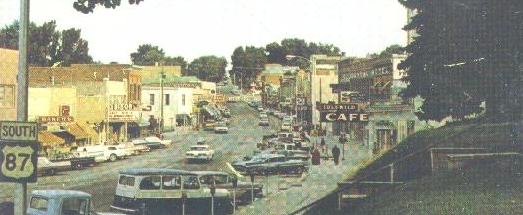

Buffalo, Wyoming, approx. 1900. Compare left photo to

1960's photo at bottom of page.

Buffalo, located at the military crossing of the Bozeman Trail across Clear Creek, traces its beginnings to Charles Buel, a native of

Wisconsin, who in 1879 began what become the area's first bank and what became the Occidental Hotel,

as above noted

featured in Owen Wister's The Virginian. The Trail leading from Ft. Laramie to Virginia City was

regarded as a part of the Great North Trail, a loose collection of trails leading from

New Mexico along the eastern side of the Rockies to Canada. Portions of the

Trail were laid out in the Reynolds Expedition discussed in Photos II. In 1863, John M.

Bozeman, attempted to trace the trail but was turned back by Sioux near present

day Buffalo. The following year four wagon trains went through from Fort Caspar, but in

1865, the Trail was closed but it was again reopened to emigrant use in 1866. The military

crossing was at the present City with the emigrant crossing about a mile

south. Following the Fetterman

fight of July 21, 1866, the trail was again closed to non-military use. [For a linked

map of the Bozeman Trail click here. Use

browser back button to return.]

Nevertheless, some civilians continued to attempt to use the Trail. Bozeman,

himself was killed in the Spring of 1867 in a skirmish with the Blackfeet

near the Yellowstone River in one such attempt.

Following the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie the trail was closed to all use until

the 1870's when,

as depicted in the following photos it became an important route into the

Powder River area from the South. the 1870's when,

as depicted in the following photos it became an important route into the

Powder River area from the South.

Left,

freight train, Buffalo, Wyo. 1884. Note use of tandem wagons.

In 1866, Ft. Phil Kearney was established 225 miles from Ft. Laramie, at the

Piney Tributary of the Powder River. Almost immedately it came under seige by the

Sioux under the leadership of Makhipiya Luta, Red Cloud, and remained so

all Summer and Fall. On December 26, 1866, a wood train came under attack only

six miles out from the fort. Capt. Wm. J. Fetterman, Brevet Lt. Col. during the

Civil War, boasting that with 80 men he could go through the entire Sioux Nation,

volunteered to lead a relief unit. Disobeying Col. Carrington's orders, he

allowed himself to be lured across Lodge Trail Ridge where his entire unit of

80 men were ambushed and killed along with two civilians who went

along to test two new Henry repeating rifles. The infantry were equipped with inferior

muzzle-loading Springfields and the cavalry with Spenser carbines.

two new Henry repeating rifles. The infantry were equipped with inferior

muzzle-loading Springfields and the cavalry with Spenser carbines.

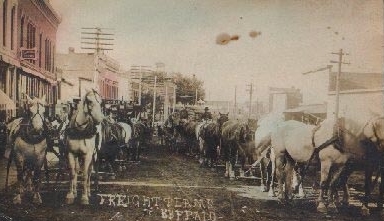

Freight Train, Buffalo, early 1900's

Note addition of telephone and electric

lines. Compare this photo with ones above and the newer scenes of Buffalo below.

In two other fights, the Hayfield Fight and the Wagon Box Fight the army was

more successful. In the Hayfield Fight, near Ft. Smith, a haying detail consisting of 19 soldiers

and 6 civilians, under Lt. Sigismund Sternberg, equipped with breech-loading

Springfields and severl repeating rifles, successfully held off a superior force,

sustaining only 3 killed and 3 wounded.

In the Wagon Box Fight, near Ft. Kearney and in which an ancestor of Sen.

Alan K. Simpson fought, a detail under Capt. James Powell, barricaded behind

behind wagon bodies that had been removed from their running gear, held off

several thousand Sioux and Cheyenne, attacking in waves of several hundred at

a time, for over four hours with a loss of only 3 killed and 2 wounded.

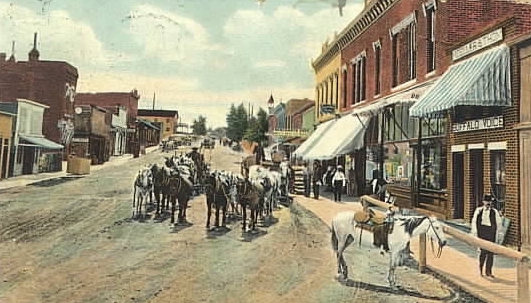

Buffalo, 1910

The offices with the striped awning are those of the Buffalo Voice newspaper. The paper

changed its name in 1925 to the News and in 1926 merged with The

Bulletin.

Fear of the Indians continued as late as the 1890's. The Buffalo Echo joined

the histeria which swept parts of the west in 1890 relating to the "Ghost Dance." On

November 22, 1890, the paper put out a extra edition reporting under the headline, "THE

MASSACRE BEGUN," that "religion crazed Redskins" had broken out of the Pine

Ridge Agency. The paper reported that 20,000 troops were being called up and that

Fort Robinson had been left unprotected. It further reported that ranchmen and

their families were "fleeing in terror." The entire issue was based on conversations with

a lady who was passing through by stage and who had no first hand knowledge, but

was merely repeating what she had heard.

The panic had commenced with an article in the Rapid City Journal of November 20, 1890,

which had reported that the Sioux were on the warpath. As a result, in

December, the governor of South Dakota activated the South Dakota Home Guard which

proceeded to kill and scalp 75 ghost dancers. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was

killed by Indian police. Some of the Sioux then fled in fear, with about 100 joining

Chief Big Foot on the Cheyenne River. Chief Big Foot, suffering from pneumonia and coughing up

blood which would then freeze in the snow, sought to lead his

tattered band of aproximately 120 men and 230 woman and children to the agency

at Pine Ridge. On December 28, the band met up with the Seventh Cavalry which surrounded it, and sought to

disarm the Indians. One Indian, Black Coyote who was deaf, did not wish to surrender

his Winchester. In an ensuing scuffle the rifle discharged wounding an officer. Immediately,

the soldiers opened fire with, among other things, four Hotchkiss rapid fire

machines guns. At the end between 200 and 350 Indians lay dead in the snow, including

women and children who were two miles from the scene. Among the dead was

Chief Big Foot who had a white flag next to his tent. Twenty-five troopers were also killed,

most by their own cross-fire. The dead were left in the snow for over a week and

then buried unceremoniously in a mass grave. The Seventh Cavalry received for its

gallantry twenty Congressional Medals of Honor. One hundred years later the

Wall Street Journal continued to refer to the massacre as the "Battle of

Wounded Knee." One of the grievances of the American Indian is that when the

Indians won, it is referred to as a "massacre," i.e. the "Fetterman Massacre." When the

cavalry defeats even unarmed Indians or Indians under a flag of truce, i. e. Sand Creek

or Wounded Knee, it is a "battle."

Buffalo, 1960's. Compare with 1900 photo above, left.

While in most areas, the Bozeman Trail is not very visible,

traces may be seen at Crazy Woman Crossing, south of Buffalo.

|